Ontario Film Company, 1930

Producer, Director, Scenario: George Thorne Booth.

Titles: Dr. Sam Atkinson.

Photography: Bert J. Bach, Frank O’Byrne.

Editors: A. Hillard Gray, George Thorne Booth.

Cast: Marjorie Horsfall, Jolyne Gillier, Frederick Mann, Valdemar Hinch, Ernest C. Sydney, Anthony Dorazio, Boyd Mount, Ivor Danish, Georgina Dean, Charlotte La Tourelle.

When The White Road first unspooled in May 1930 at Toronto’s Belsize theatre, behind Mount Pleasant cemetery, it was a six-reel silent feature. It survives as sixteen feet of 35-millimetre, tinted, nitrate stock comprising only four shots. Augustus Bridle reported in the Toronto Daily Star, “It has many defects; sometimes poor lighting; occasional blurred scenes; now and then a weak spot in continuity; some very long and over-rhetorical titles.” Producer and director George Thorne Booth defended the picture as “an experiment … to see what we could do to make a feature film at low cost. The total cost was $3,000. The lighting equipment I made myself at a cost of $120.”

Even though released as late as the sound era, it was reported to be the first feature-length film wholly shot in Toronto (though it might have contended with Blaine Irish’s Satan’s Paradise, from eight years earlier). The story, however, opened at a Hong Kong market. A Chinese boy is attracted to a trinket that Joan Trethway, the daughter of a traveller, is wearing and tries to take it. Lou Ming’s father intends to kill him for his crime—according to the teachings of Buddha, supposedly—when the girl pleads for mercy, and the grateful boy promises he will never forget her kindness. Years later, now in the underworld and the opium dens of Toronto ruled by the evil Wong Chang, Lou Ming makes good his promise, finding himself, as Bridle put it, on “the white road of sacrifice and elevation of soul.”

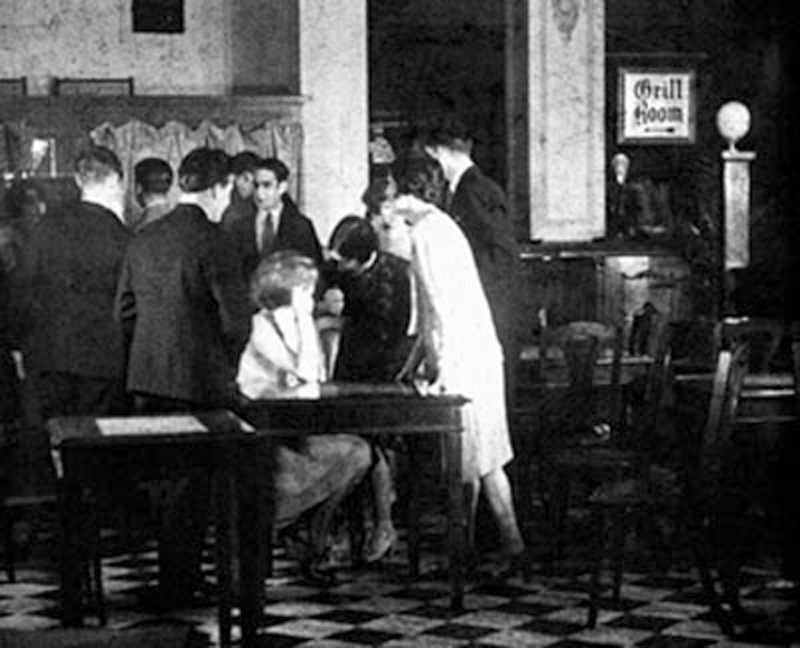

Shot on the city’s streets and in residences, restaurants, and other establishments, including Ryan’s Art Galleries, the film featured Toronto locales. The producers also resourcefully used locations available to them to cheat foreign settings, shooting China-themed displays at Eaton’s for the Hong Kong streets and bazaar, and using the department store’s boiler room as a ship’s stokehold. A Yonge Street restaurant stood in as the location for a “’whoopee’ party in a café in China.”

Although a premiere was announced as imminent in April 1929, the film was first screened over a year later, on 7 May 1930. Then, on the 21st at the Belsize, it was presented with more or less synchronized musical accompaniment. The band accompanied the picture effectively with such tunes as Weber’s “Invitation to the Waltz” and Saint-Saëns’s “Dance of the Skeletons,” but faltered when it continued to play a waltz while characters in the film had started to foxtrot. Bridle reported that although Toronto moviegoers might have become accustomed to talking pictures, this audience demonstrated no impatience with the return to the conventions of silent cinema.

Several of the film’s principals represented theatre presented at Hart House and the Academy of Dramatic Art, established in 1927 and operated by the British actor George Dickson-Kenwin (usually known just as Dickson Kenwin), whom Booth later cast in a short film, The Bells (1932). With his Academy Players, Dickson-Kenwin presented productions at the Little Playhouse, at 142 Bloor Street West, with a capacity of sixty-six billing itself as the smallest theatre in the world. Ernest Sydney, who portrayed the adult Lou Ming, and Boyd Mount, who played Joan’s father, were favourites in Academy shows. As well, in 1928 Dickson-Kenwin proudly announced that he had “secured the services of Mdlle, Jolyne Gillier, graduate of the Leonidoff Russian Ballet, to teach Dancing, Grace, Deportment.” Regularly featured at the Uptown theatre and sometimes billed as “Miss Canada,” she had sufficient celebrity and was so “much-admired,” as the Star put it, that the paper prominently featured her marriage to Toronto-resident New Yorker Lucian Haugwitz on the front page of the second section, billing the event, “Ballet Beauty Weds Park Ave. Heir.” Although they married only a week before the premiere of the picture that featured Jolyne as Joan, the wedding notice said nothing about The White Road.

Originally credited to Sydney and his friends, “a group of enthusiastic amateurs” who had decided to make a movie eighteen months before, the film was also something of a springboard for Booth’s ambitions, as well as the centre of a spat between the two men. Booth was establishing his own company, Booth Canadian Films Limited, and he outlined his plans to produce talkies—two-reelers, as a way of starting small—movies that would be “Canadian in every foot and every dollar.” Booth’s new affiliation had been omitted from press coverage, and Sydney complained that Booth had been misrepresented as speaking for the Ontario Film Company, of which Sydney was president. “A charter member and managing director” of the company, Booth resigned after the film was completed. He distanced himself from The White Road, claiming “no personal intention of trying to market the film whatever may be done with it by anyone else,” and noting, “Since then present members of this company have made alterations which undoubtedly cost more money. This, however, in no way concerns me.” It appears, in fact, that no one tried to market the film. The Star optimistically saw the benefits in “two Canadian film companies instead of one,” but the Ontario Film Company appears not to have produced other pictures.

Booth—“small in stature, with bright eager eyes, and radiating nervous activity”—simultaneously completed a second Toronto-based film, which was presented only ten days after The White Road’s public screening. Also silent, Barriers, proposed as a three-reeler and produced by the Central YMCA’s Amateur Cinema Club, was made to describe the activities of the organization. YMCA secretary H. G. McKinley wrote a scenario revolving around Kenyon, formerly a young athlete, now a “dope-fiend … fast in the toils of Chang Yat, lecherous king of the Chinese underworld.” Fallen low and involved in the kidnaping of a white woman, Kenyon chances on his old YMCA pin, and memories of his healthier days trigger his remorse, his decision to overpower the crime boss, his rescue of the victim, and his return to the Y. Although Augustus Bridle had said of The White Road that “there are no such opium dens in Toronto as that of Wong Chang,” they certainly existed in the contemporary Canadian imagination. These two films, along with Secrets of Chinatown (1935), produced a few years later in Victoria, suggest a contemporary fascination with the Asian as exotic, but also heightened levels of racially-based moral panic used for narrative convenience.

As a feature film located in Toronto, a rarity at the time, and as a picture involving some notables in the city’s theatrical and performance sector, but also as a work incorporating contemporary social attitudes and problems, The White Road has value as a cultural document that makes regrettable its loss, the remaining shard barely a reminder.

Sources: Classified advertisement, “Important Announcement…,” Toronto Daily Star, 10 March 1928: 35; “Release Toronto Picture for Public Viewing Soon,” Toronto Star Weekly, 20 April 1929: 2; “Toronto Girls Appear in Films,” Toronto Daily Star, 20 January 1930; “Show Motion Picture Made By Amateurs,” Toronto Daily Star, 8 May 1930: 7; “Ballet Beauty Weds Park Ave. Heir,” Toronto Daily Star, 15 May 1930: 25; “Much-Admired Dancer Married Wednesday,” Toronto Daily Star, 15 May 1930: 30; Augustus Bridle, “Toronto’s First Movie Revives Silent Drama,” Toronto Daily Star, 22 May 1930: 17; “Y.M.C.A. Cinema Club Produces Smart Film,” Toronto Daily Star, 31 May 1930: 30; “Toronto’s First All-Amateur Film Screened,” Toronto Daily Star, 31 May 1930: 35; “Film Company in Ontario Mapping Out New Program,” Toronto Daily Star, 31 May 1930: 9; “Booth Canadian Films to Ontario Film Co.,” Toronto Daily Star, 14 June 1930: 4; “Tiny City Theatre Marks Anniversary,” Toronto Daily Star, 15 November 1930: 12; “Complete Round of Delight” and advertisement, “See Miss Canada In Her Demonstration of the Famous Stewart Warner Radio, [St. Catharines Standard], nd [c 1930], collection of Robin Ferry; “Littlest Playhouse To Do Indian Drama,” Toronto Daily Star, 14 March 1931: 10; “New Canadian Film Pleases At Preview,” Toronto Daily Star, 6 April 1932: 40; “Uptown Plays Bells,” Toronto Daily Star, 25 June 1932: 7; Robert Barry Scott, “A Study of Amateur Theatre in Toronto: 1900–1930,” MA thesis, University of New Brunswick, 1966; Peter Morris, Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema, 1895-1939 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1978).

Blaine Allan

Film Studies

Queen’s University

Kingston, Ontario

allanb @ queensu.ca

[The White Road : excerpts] link to the Library & Archives Canada database: https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/CollectionSearch/Pages/record.aspx?app=filvidandsou&IdNumber=25355&new=-8585761031149854044

Record Information – Details;

Fonds/collection: UNIDENTIFIED

Accession number: 1973-0141

Media: Film

Production date: 1928/1929

Release date: 1930-05

Production company: Ontario Film Company

Production credit: producer/director/scenario/editing, George Thorne Booth; photography, Bert J. Bach; Frank O’Byrne; editing, A. Hillard Gray

Cast credit: Majorie Horsfall, Joline Gilliere, Frederick Mann, Valdemar Hinch, Ernest C. Sidney, Anthony Dorazio, Boyd Mount, Ivor Danish, Georgina Dean, Charlotte La Tourelle

Country of production: cn

Language: Silent

Notes:

1. The creator of this film, George Thorne Booth, died on 7 August1957, at his summer home in Bracebridge, Ontario (see obituaries in The Canadian Film Weekly of 21 August 1957, p. 4 and the Toronto Star of 9 August 1957 pp. 19 and 39.

2. This is the only footage known to have survived for this film.