An essay by Stephen Lee Naish about his soon to be released book, Music and Sound in the Films of Dennis Hopper, 1st Edition, Copyright 2024.

American film actor and director Dennis Hopper was a notorious symbol of the excesses of the 1960s. His rise and fall within the New Hollywood era could be considered a cautionary tale of what occurs when genius, ego, drink, and drug dependency collide. To summarize, from 1955 to 1965, Hopper worked within mainstream Hollywood film, appearing predominantly in Westerns until a disagreement on how to deliver a line of dialogue with director Henry Hathaway on the set of The Sons of Katie Elder (1965) led to his expulsion and blacklisting for being too difficult to work with. For a time, Hopper floated around the art scene of Los Angeles and New York, documenting with his trusty Nikon camera, and buying up the early artworks of Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol. Hopper would appear on occasion in exploitation films such as The Trip and The Glory Stompers (both 1967). It was his friendship with actor Peter Fonda that led to his directorial debut Easy Rider (1969). The film might just have been a more meditative take on the biker flicks that were popular in the mid-to-late 1960s, yet helped along by the glorious cinematography of László Kovács, the inventive use of popular music within the soundtrack showcasing the likes of Steppenwolf, Bob Dylan, and Jimi Hendrix, and the notorious consumption of drugs, Easy Rider became a cultural phenomenon, a massive box-office smash, and a milestone in American New Wave cinema and the wider pop culture.

With this success, Hopper negotiated with Universal Studios a then unprecedented million-dollar budget, and final cut on his next directorial film. He flew off to Peru with his friends, dealers, and various other hangers-on to make The Last Movie (1971), a film that explored the impact of a Hollywood film production on the indigenous population of a remote village. As well as directing and co-writing the screenplay with screenwriter Stewart Stern, Hopper cast himself in the lead role as a cowboy stuntman named Kansas. The film shoot was a disaster of epic proportions. Drugs, sex, and debauchery filled the days and nights. The post-production was even more unwieldy and drawn out by various hedonistic distractions. The documentary film The American Dreamer (1972) chronicles this disarray. The Last Movie was written off at the time of release as an indulgent and pretentious waste of time. It was given a two-week theatrical run and then buried for decades after.

Hopper was jettisoned yet again for a second period of exile that lasted the rest of the 1970s and deep into the 1980s. A figurehead of change within the filmmaking industry was also one that almost blew it up.

Not invited to act in mainstream American films Hopper found sporadic work in low-budget independent films such as Henry Jaglom’s post-Vietnam War film Tracks (1977). But his exile took him further afield. He appeared as suave conman Tom Ripley in German director Wim Wenders’ The American Friend (1977), and starred as roving Australian bushranger Daniel Morgan in Philip Mora’s Mad Dog Morgan (1976). However, the trifecta of oddball European films L’Ordre et la sécurité du monde (1977), Couleur Chair (1978), and Las Flores Del Vicio (1979) showed that Hopper was as far away from American movies as he could get. Many cinema audiences were astounded to find out he was still alive when he appeared as the PTSD suffering photojournalist in Frances Ford Coppala’s Apocalypse Now (1979). This mainstream role was a blip in the long exile that Hopper was entrenched in, and his jittery, scatterbrained performance was an extension of his burned-out, drug-addled, real-life persona.

In the late 1970s, Hopper was cast in a Canadian television movie that had the working title The Case of Cindy Barnes. The narrative at this point concerned a young girl who is saved from her abusive parents and rehabilitated by a child psychologist, played by Canadian actor Raymond Burr. Hopper was originally cast as Cindy’s father. The original writer and director Leonard Yakir jumped ship two weeks into production when it became clear that no usable footage had been shot. The film was almost abandoned until Hopper convinced the financial backers to let him take over production. Feeling that all was lost, they allowed Hopper to not only direct the film, but re-write the screenplay, recast various roles, and offered him final cut if the production didn’t go over budget. It was also deemed essential that Raymond Burr remain in the cast to ensure the film’s status as a Canadian tax shelter production.

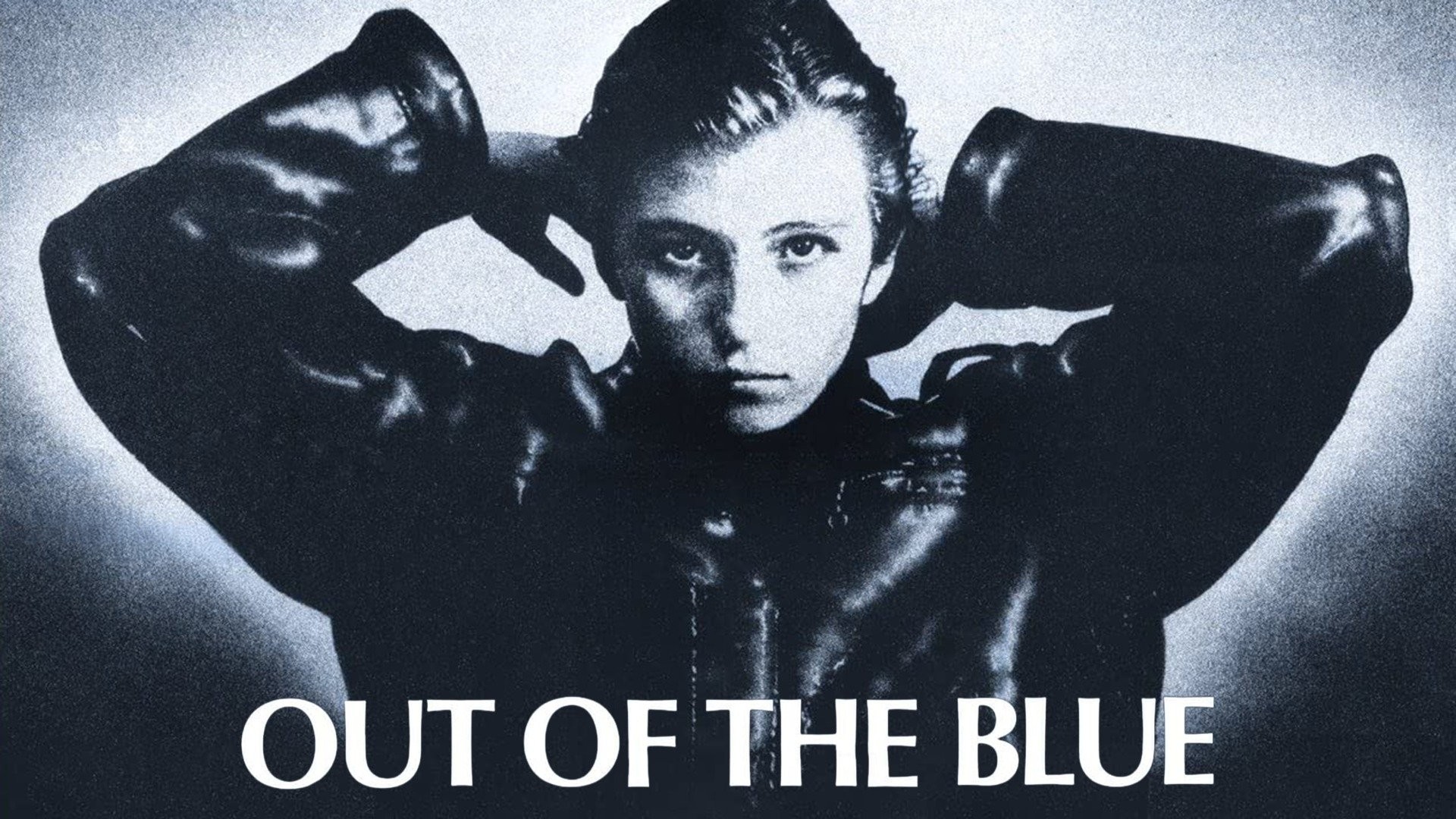

In a weekend of creative intensity, Hopper rewrote the screenplay and shifted focus from Burr’s psychologist character to the young Cindy Barnes (renamed Cebe), who was played by American actress Linda Manz who was fresh from critically acclaimed performances in Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978) and Philip Kaufman’s The Wanderers (1979). Instead of a character that needed saving, Hopper rewrote Cebe as a self-reliant punk rock girl. Hopper’s role as Cebe’s dad, was beefed up with a tragic backstory, and an appetite for drugs and booze. Actress Sharon Farrell’s role as Cebe’s promiscuous and heroin addicted mom was also placed central to the story. Hopper retitled the film Out of the Blue after Neil Young’s 1978 song “My, My, Hey, Hey (Out of the Blue)”. The song would become a signature theme within the finished film.

Out of the Blue centers on Cebe, a 15-year-old girl obsessed with tragic male icons such as Elvis Presley and Syd Vicious. Her father Don has been serving five years in prison for a drunken accident that involved crashing his truck into a school bus while intoxicated. He is scheduled for parole. Her mother, Kathy works as a waitress and has a steady relationship with the owner. Cebe believes that Don’s release will reunite her family. It almost does. Until Don returns to the bottle and the horrors of Cebe’s past sexual abuse at the hands of her parents reemerges. She runs away to the city, here played by the East Hastings district of Vancouver. She joins Vancouver punk rockers The Pointed Sticks on stage and, is nearly sexually assaulted by a cab driver, escapes, and crashes a car into a ditch. Cebe stabs her father to death when he attempts to rape her and leads her mother out to the abandoned rig with a stick of dynamite. She blows herself and Kathy up in a roaring blaze. “Better to burn out than to fade away” as Neil Young’s signature song reminds us as the credits roll.

Out of the Blue was not the calling card to the Hollywood bosses Hopper hoped it would be. The finished film was a nihilistic piece of cinema. The themes centered on drugs, alcohol, sexual abuse, incest, and the destruction of the nuclear family. It was a generational call and response from the punks back to the hippies. Cebe is not saved. Everyone dies, and their world goes up in literal flames. The film channeled the urgency, extremities, and two-fingered salute of punk rock pessimism and Cebe, as portrayed by Manz, is a tough feminist icon in the same vein of radical feminist Valerie Solanas.

It was, in some respects, ahead of its time. The film could have sat comfortably among the 1990s indie new wave of films like My Own Private Idaho (1991), Totally F***ed Up (1993), The Doom Generation (1995), and Crash (1996). These films explored the darker and more perverse side of modern life. Coming, as it did, at the beginning of the Reagan Presidency in the United States and a more conservative outlook towards ‘moral majority’ family values, the film felt off-kilter and was mostly shunned by critics (though there were notable exceptions) and deemed unsellable. The Cannes Film Festival invited it to run in competition for the Palme d’Or, but it had to be screened as a Dennis Hopper film and not as an official Canadian entry. However, there were audiences who appreciated its brutal candor and punk rock energy. The film was shown in small independent cinemas at late night screenings and jumped from one slowly degrading VHS cassette tape to another as admirers passed the film on.

In the proceeding decades the film found its vocal champions. Actresses Natasha Lyonne and Chloë Sevigny helped promote a Kickstarter campaign to restore the film to a 4k digital print. The campaign exceeded its goal and the film’s restoration by John Alan Simon and Elizabeth Karr of Discovery Pictures played to audiences worldwide and was issued with extensive supplementary material on DVD and Blu-ray. The film found its acclaim and audience adoration four decades after its original release.

And so, what became of Hopper after his Canadian adventure? Drugs and booze dominated until an incident on the set of the sexploitation film Jungle Warriors (1984) saw Hopper so strung-out he wandered off naked and alone into the Mexican jungle and when he was found by the film crew and the Mexican police, he was delirious and begging to be shot dead. This episode saw Hopper admitted to a rehab hospital for several months.

Clean, sober, and with a newfound appreciation for his craft, Hopper faced a renascence upon his return to acting. 1986 was a bumper year with roles in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, Tim Hunter’s River’s Edge, and David Anspaugh Hoosiers, which saw him nominated for Best Supporting Actor in the following year’s Oscars. He continued to act within mainstream films and indies alike and returned to the director’s chair on four more occasions starting with Colors (1988), Catchfire (1990), The Hot Spot (1990), and Chasers (1994).

Since Hopper’s death from pancreatic cancer in 2010 at the age of 74, the focus has been shifted from his film work towards the extensive archives of photographs and visual art he produced over his lifetime. Numerous monographs have been published and exhibitions have been held across the world. Even The Last Movie has had reassessment, and an extensive Blu-ray/DVD reissue, and a soundtrack release on vinyl. It’s no longer deemed a catastrophic failure but a brave stab at a Hollywood-funded avant-garde film.

Out of the Blue remains Dennis Hopper’s most vivid and exciting directorial film. A straight- forward summary of how one generation unknowingly damaged themselves and the subsequent society that unfolded inflicted emotional trauma upon their kids. By using punk music and punk attitude, the film denounces the very culture in which Hopper emerged from. That is quite a statement to make.

OUT OF THE BLUE 4K Restoration & Theatrical Re-release. Click on the image to view the video…

© 2024 Stephen Lee Naish – https://linktr.ee/ste_lnaish

Click on the image to order or view more details from the publisher.

(Available for pre-order on February 16, 2024. Item will ship after March 8, 2024).

Hi, Stephen: Great article! One correction for the record is that Natasha Lyonne and Chloe Sevigny did not initiate the Kickstarter campaign that helped support the restoration. The Kickstarter was spearheaded by my wife and producing partner Elizabeth Karr. Elizabeth happened to hear Natasha on NPR talking about her love of OUT OF THE BLUE and especially her admiration for Linda Manz’s astonishing performance. We ran into Natasha at a Netflix event , told her of our plans for the 40th anniversary restoration/re-release – and at our request she and Chloe (who Natasha recruited) supported the restoration with a donation outside the successful crowdfunding campaign and came onboard as official “presenters” to help promote Dennis Hopper’s OUT OF THE BLUE to new, younger audiences. – Chloe also supported the restoration by attending the Venice Film Festival premiere of the restoration in 2019 and Natasha attended the NYC theatrical premiere and did a Q&A with us on opening night – John Alan Simon, restoration producer OUT OF THE BLUE (1980).

Thank you for your comment John. As I understand, Stephen has replied to you, and I have updated the post with a link to the 4K restoration at the end of the article. Dale.